First velocars were constructed by Charles Mochet in Paris in the 1920’s. Velocars were quite popular during the German invasion, and the idea was adopted to Sweden. During the war, though Sweden was not involved, the use of gasoline for private cars was prohibited, and young men started looking for a substitute for the car. Soon the idea of making velocars (called cykelbil in Swedish) of bicycle parts and fairing of either plywood, canvas or aluminium spread through the country, and around 10000 velocars were built in the 1940’s. National championships were organised all through the decade, and the velocar soon developed light and fast means of sports and traffic.

Backgrounds

After the World War II the idea of the velocar came from Sweden to Finland. Most of the Finnish automobiles took part in the war, as well as young men. Only few of them were returned to civil use, but in that situation it was not the biggest problem. There was a shortage of most things like food, clothing, and even bicycle tyres.

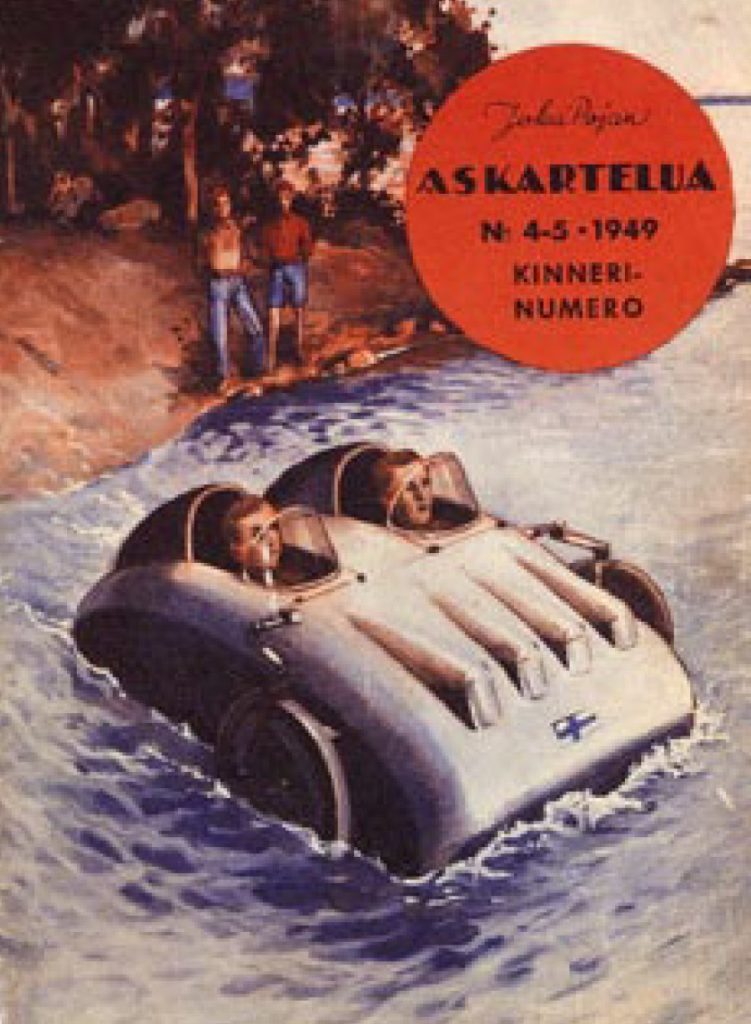

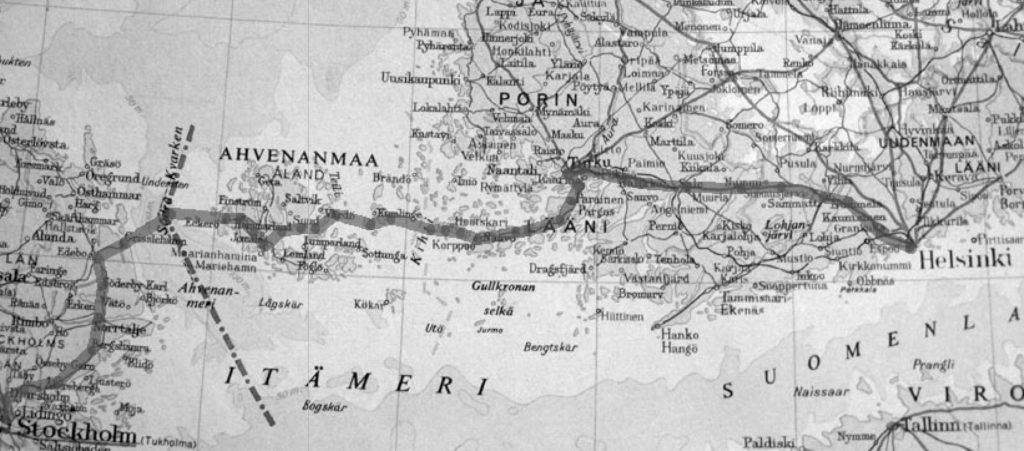

After the war, in 1946, as things turned normal again, also some young Finns took part in the Swedish velocar championships. In next two years half a dozen velocars were built in Finland, and a couple of youth magazines published velocar design plans in 1948. The Swedes also came to show their velocars in an indoor competition. This promotion caused the break through of velocars in 1949. Velocar clubs were founded, and the first Nordic Championships were held in Helsinki. In the summer of 1949 two young men cycled from Helsinki to Stockholm – not only on roads but over the Baltic Sea. They became heroes in Sweden and in Finland.

To cross the sea was a consequence of a bet, not only lust for travelling.

Poikien Keskus (the boys’ centre) was an association that tried to gather boys of age 8-18 to have practical hobbies in a Christian community. The chairman of the association was writer Sulo Karpio, and his son Reino Karpio, age 30, was responsible for the crafts club.

In the country where lakes often make straighter routes than hilly roads, it was natural to think of an amphibian velocar. Reino Karpio, the young craft teacher experimented with bike parts and wood and during the long winter finished the velocar that was successfully tested in the heart of Helsinki in spring of 1949. The amphitrike was introduced to the public also in the Joka Poika magazine. The front page illustration was drawn by Matti Näränen, a young boy working for the club.

The design

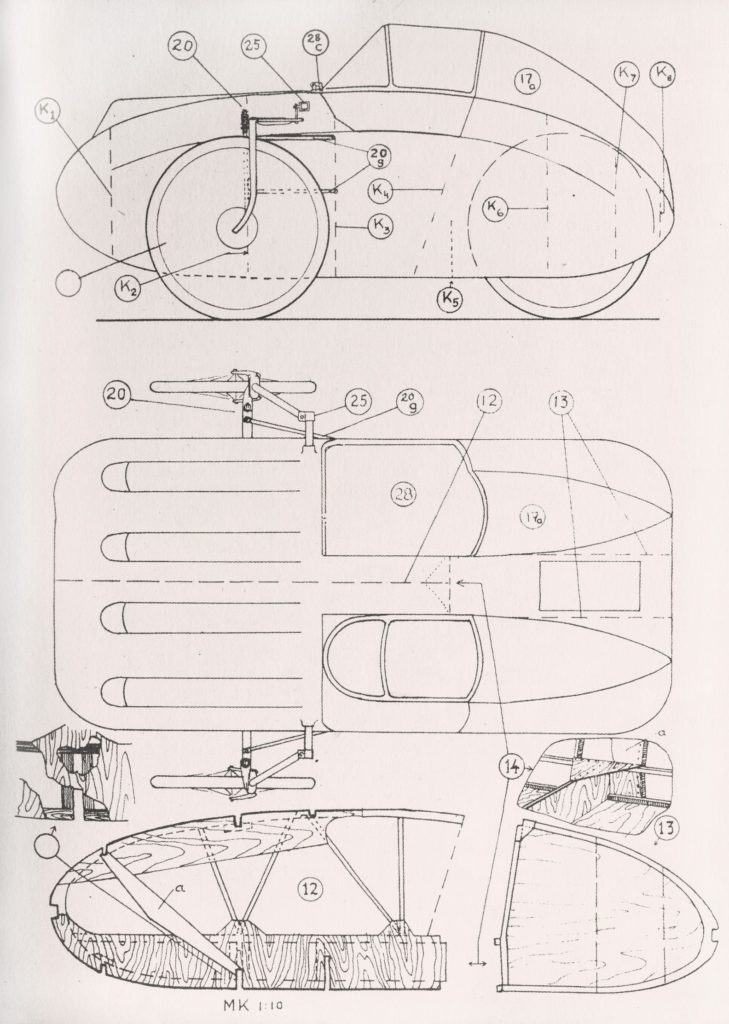

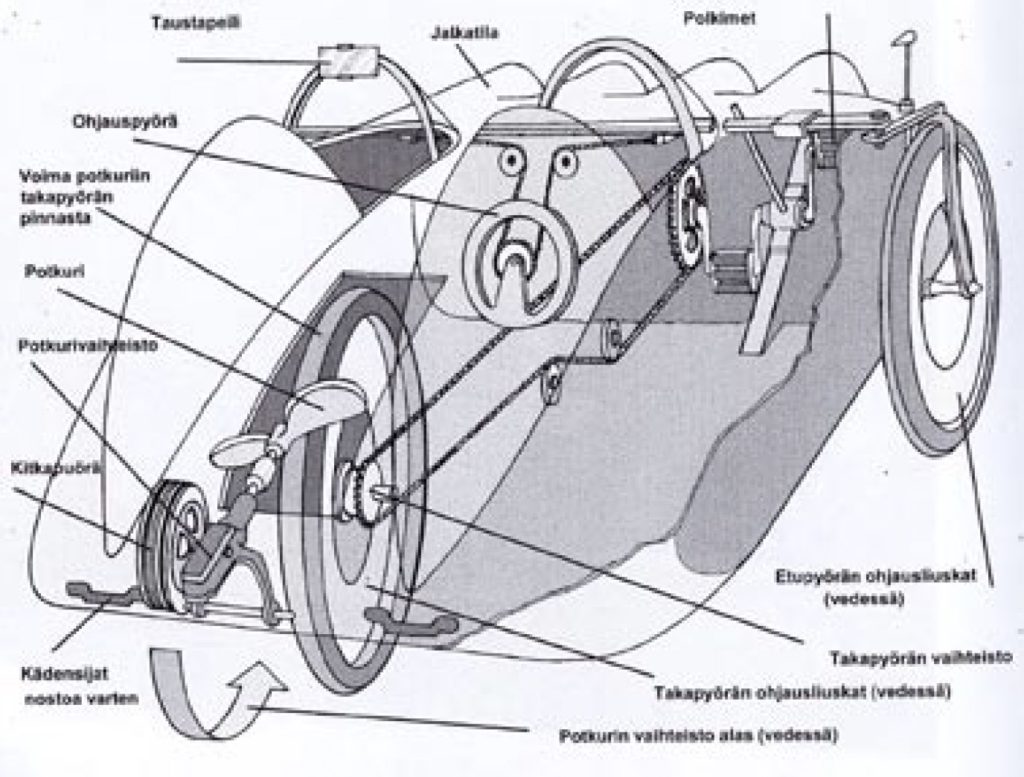

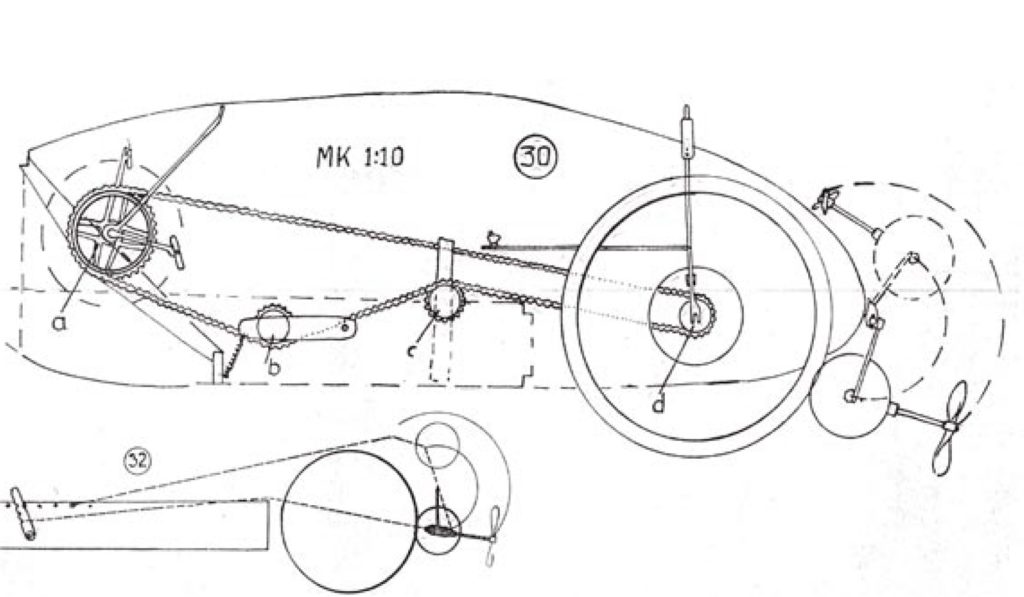

The basic design of this amphibian was a two-person recumbent tricycle with two wheels in front. It was front steered, rear-powered, had a friction propeller at the back and plywood rudders on the front wheels. The bottom brackets of the two riders were connected together with a third bottom bracket in the middle, from which a single chain transmission lead between the riders to the rear wheel. All the wheels were 28 inch size, taken from popular upright bikes, rear wheel equipped with Sturmey-Archer three-speed hub.

For steering there was a plywood steering wheel between the riders, and a chain to turn the steering axle. The seats were only a piece of canvas hanging from the frame bars. Around the riders there was a fairing made of 1.2 mm aeroplane plywood. Part of the upper body was covered with parachute fabrics and painted. All this only weighed 65 kilos. The plywood structure was used both in aeroplanes, even in some of the war planes that Finland used in the World War II, and in canoes. So it was well known to resist even water.

The trike was exhibited in several shows around Finland during the spring of 1949. It was also invited to the World Sports exhibition in Stockholm by Teknik för alla – magazine that made publicity to velocars in Sweden.

Blueprint of the two-seat amphibian velomobile from Finland

Perspective section shows some details of the chain guiding. Drawing by Matti Näränen. Kinnerimatka, 2002.

Test ride

The bike was ready to test in the summer of 1949. There was an opportunity to really let it go, to show its properties in speed. The first and only Nordic Championships in velocar riding were held in Helsinki in June. Teams came from Sweden, Denmark and Finland. Competitions were held for single men and women and for tandems, both in one mile and in five kilometres. The amphibian trike took part, this time driven by Tuominen and Rihtamo. The Swedes who had been developing and competing with velocars already since 1940 took all the wins, but the Finns were not bad either.

The amphitrike was also tested in water in the centre of Helsinki as a film photographer wanted to make a short film of it. The film was later shown in news flash at movies. It proved just as good as it was planned. It was water resistant, and the friction propeller helped to cross the small Tölö bay in the heart of the city.

The adventure

To cross the sea was a consequence of a bet, not only lust for travelling. A visitor in a show couldn’t agree with the nautical properties of the trike, and Karpio took the bet. If he cycled to Sweden he could also take part in that sports exhibition. Karpio was trying to get sponsors to cover the costs, and at last got a sports drink producer Ranamalt to promise a small amount of money, if he ever returns.

It was going to be dangerous, so it was not that simple to get the other seat filled. At last Matti Näränen, a 22 years old boy who was working for the boys’ centre promised to try. As he was not full aged, he had to get a permission of travelling abroad from the police, the army and his parents. The passport was only valid for a month. Actually one of the biggest tasks of the adventure was to overcome certain problems with passports and the customs. But Reino and Matti met some problems en route, too. Not only the broken gears and propeller, but also social doubts: they were fishing illegally and the bike was considered as a secret weapon of the coast guard.

The departure took place at 4 a.m. on July 3rd 1949. Reino and Matti took the new road towards Turku in good speed, and everything went well – in the beginning. After some 20 km they had to stop for repair. They were quite enthusiastic to overtake an upright bike, rode downhill in high speed, too fast to steer on the loose gravel road. They ended in a bottom of a ditch and lost the rear wheel. They were waiting for several hours to get help and repair it.

Some smaller maintenance and repair was done before they entered Turku the next afternoon after some 200 km of riding. But actually they did it quite well; the amphitrike was making 45 km/h in good conditions. But uphill made them sweat. In Turku the boys were not allowed into a hotel because they were considered being sweaty and muddy. Finally they were taken to a hostel where they could wash and change clothes.

The sea

From Turku they headed trough Parainen to Nauvo and Korppoo Islands. At the time there was no brigde, so they had to enter the sea. The first impressions were positive, encouraging. The bike was swimming quite high thanks to its light weight. The resistance was heavy, though, and the speed had to be kept low. The aerodynamic of the bike was good on the road, but ships are built in another way.

The bottom of the velocar was flat and it glided easily on water. The propeller was put down, and the back wheel kept the propeller running. The power was changed via drill wheels. When entering the land again, the propeller was taken up with a cable into the box between the bikers. The idea was superb, but the parts were not strong enough to do it out on the sea. It was impossible to ride faster than 6 knots. Also the shape made it uneasy to steer. There were kind of fins in the front wheels, but they did not work if it was windy.

From Korppoo they started out to open sea, Kihti. The wind started to blow against them, and steering was impossible. Luckily they had paddles with them and they managed to get into a small island, otherwise they could have been soon found in Estonia. While trying to get the bike to land, Matti fell down on a slippery rock, got under the bike and had a wound from the propeller in his foot. The sea was soon red in colour, but they could save the bike. Matti had a scar for the rest of his life.

They made a fire and decided to have a rest. They were sleeping in the bike. The wind was gone in the morning, and as they were relaxed, they had a new try to cross the Kihti. The propeller was a little damaged, too, and they were mostly using the paddles to reach Kumlinge. There they could fill their luggage with food and medication to reach the actual Åland through Vårdö. These problems all took its time and the planned 10 hours trip over Skiftet turned out to be four days.

At last they decided it was a sailboat, because it rode on the water, didn’t have a motor and it was taken by the wind.

Tourism was not unknown in Åland already in the forties. Normally tourists took their luggage with horse carriages, not with velocars. So the boys had fun to notice an old, slowly moving lady jumping up in the air and running into the woods as they came into sight. As they rode from island to another, they stopped in a small island and asked for water and were replied: you will find water in the holes of the rock. But people were friendly enough to lend them some tools to make some adjustments for the bike.

In Mariehamn the boys were sleeping in a hostel, and as the local newspaper had made a report on the journey, they were given a double room instead of dormitory beds. They cycled to the airport where the velocar won great interest among male passengers. A local cab driver had a veteran taxi, and he was very keen in special mobiles. He gave the boys a lot of help to get ready for crossing over to Sweden. He also followed them to Eckerö customs station to help with the formalities. And help was needed.

The customs station in Eckerö is an old post office building of special importance. It was built in 1830’s to link the mail between Sweden and Russia, under whose rule Finland used to be since the war 1809. The mail was delivered between the countries daily with small sail boats. Now the building was used for customs as well. It was not easy to get through the formalities: what they rode was not a boat, not a ship, not an aeroplane. In which column could they put the cross? There was no column for velocar or bicycle. At last they decided it was a sailboat, because it rode on the water, didn’t have a motor and it was taken by the wind.

To Sweden

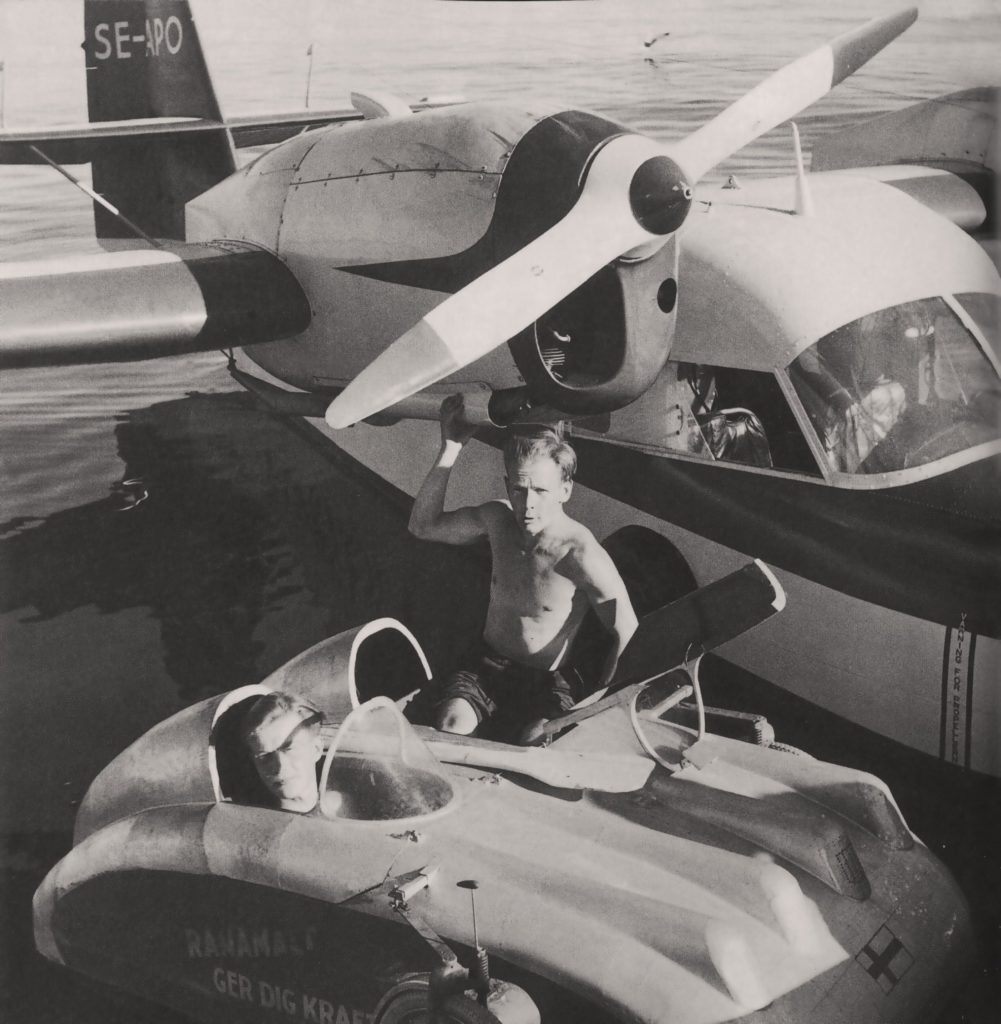

After Åland they started to cross the open sea in the evening after having waited the storm to settle down. News of their attempt had reached Stockholm press, and the boys were fetched by a seaplane and a fishing boat filled with journalists two and a half weeks after they left Helsinki.

In the dusk of a Friday evening Reino and Matti set out to the sea. There were actually no ships running during the week-ends to avoid staying in harbour over Sunday. Reino had thrown away their life west, two car inner tubes, to spare weight, and they didn’t have paddles either.

After 15 km they landed to repair the propeller in Signilskär pilot station, and the poor English speed hub was hammered to the chain wheel so they didn’t have gears nor freewheel. They stayed over the daytime on the furthern most island of Åland, and continued their trip on Saturday evening.

After Signilskär they didn’t see lights or lighthouse for a long time, because they were riding so low. They reached Märket light house, only they could see it when already near. Behind the light house there seemed to some other light too – a ship?

They didn’t have own lights either, though it was meant to cross the sea during the night. Fortunately the Nordic nights are light in early July. They had a home made spirit cooker, which Matti lighted, as the ship was seen in a distance. It came nearer, and you couldn’t believe their light was seen. Anyhow, the ship passed them just a couple hundred meters far. The ship waves made them swing, but that was the only trouble, they didn’t see any other boats during the night.

The night was clear, and fog was grown in the morning for a short period, but as the sun started to warm it became clear. And as they had sight again, they first saw a fishing boat coming nearer, and later an aeroplane. Both were filled with journalists who wanted to have the first reports. The seaplane had already made photos of them in Åland, but didn’t get permission for landing.

They entered Grisslehamn after having done around 21 km during the night in an open sea in a nice weather, a little tired. But the welcome was warm hearted. They were taken to the customs and poured some refreshment. Then they were lead to a restaurant by the sea, where they met hundreds of eager people wanting to see their heroes. Later on Reino took some of the local people for a test ride on the sea.

The following day they were taken to Stockholm with a lorry. The velocar was put on show in Skansen people’s park in an sports exhibition, where his royal highness prince Bertil met the heroes. The boys were interviewed about their experiences before a big audience. They could see a replica of an old Viking boat and met the crew that later tried to cross the Atlantic, but was not as lucky as they – it never came through.

The adventure had taken a whole month, and their permission to stay abroad was ending. On July 30th they took the ship Oihonna to Helsinki, with the velocar on the deck. Their velocar was later on show in Stockmann department store, not in its former glory as it was already damaged in Stockholm after it was left unguarded over night in the exhibition.

One of the disappointments Reino and Matti had back at home was to learn that their only sponsor Ranamalt sports drink had bankrupt meanwhile and they didn’t get the awaited money. The velocar also had some bad luck later on. After a few shows it was given to the Technical Museum of Helsinki, where it disappeared in the 80’s. This was quite a loss for the Finnish bicycle history and expedition. It was probably one of the very few velocars survived of the hundreds of those we had in the 50’s. The only one known was found in August 2007 in Eastern Finland.

Photo album of Matti Näränen

Epilogue

Every generation need its heroes. The undying Finnish heroes have mostly been sportsmen and designers, but there is space enough for short-time heroes of other professions. Reino and Matti made their adventure in the after-war years before the economic rise. In those poor days it was good to learn that you could reach headlines with something like a self-made plywood velocar, you could travel abroad with our muscle power, and you can be a hero among the Swedes, who were considered rich and proud people. Sweden was not involved in the war, and voluntary help was sent to Finland during the war and time of rebuilding. Declaration of two young Finns as heroes in Sweden can be considered as mental help to the neighbouring nation that was fighting back its economic and political space among nations.

Nobody followed the boys’ example, not Swedes, not Finns. The task was more dangerous than you could think. Probably it was only good luck they came trough after all, as the sea can be very cruel. It was on the same route that the Estonia was drowned in a storm 45 years later. Also the interest in human powered vehicles soon vanished almost for 50 years only to start anew in the 1990’s. Travelling abroad was much easier with the car ferries that began to take Finns to wealthier Sweden in the early 60’s.

Not even Reino and Matti tried their limits in this field later. Matti Näränen never entered a velocar since, but he was very interested in human powered vehicles and read all the scientific articles he runs into. He died several years ago.

Reino Karpio continued with bike travels, he took his way for instance to Morocco 1952, but he was soon more interested in sailboats. He made himself seventeen of them, mostly catamarans and trimarans. Reino died in Helsinki a couple of years ago in the age of 83.

See also the old videos of Finnish velocars which have been published some time ago.